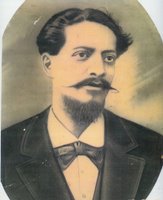

Born September 1, 1888, in Canada Morelos, Puebla (State), Mexico

Died September 11, 1937, in Mexico City, Mexico

My grandfather, known to all as simply "Cayetano" HUESCA, had an ingenious way of solving arguments between his 11 children when they were young. He would hand them newspapers and assign them to clean the windows of his hotel in Orizaba, one child working from the inside and the other on the outside. The result was that not only did he and my grandmother have some of the cleanest windows in Orizaba but the children, forced to look at each other through those windows, eventually burst into laughter, forgot their differences, and learned to work together.

This love for his family, sense of fairness and strong work ethic permeated Cayetano's life. I never met my grandfather but have felt close to him all my life because, in part, of my own father's deep reverence and esteem for him. He loved his family deeply and was an honest and hard worker who would have been proud of his children's strong family values, character, successes, closeness to and support of their mother and each other.

Jose Gil Alberto Cayetano Huesca was one of six children born to Jose Enrique Florentino HUESCA and Maria de la Luz "Lucecita" MERLO, in Canada Morelos, Puebla. He learned to work with wood from his father, who was a master wood craftsman, and he showed an interest early on in mechanics. How he came to Veracruz, I do not know. One day, however, needing a cup of coffee and a pan dulce (Mexican sweet bread), he walked into a small bakery-cafe in Orizaba, owned and operated by my great-grandmother, Maria (nee Amaro) PERROTIN. When he left, he had filled not only his stomach but also his heart, having fallen in love with Maria's beautiful daughter, Maria Angela Catalina PERROTIN. The two were married shortly afterward in 1908 and had the first of their eleven children in 1909.

A humble man, his actions spoke volumes about his life. He was first and foremost a devoted husband and father, a devout Catholic, a hard-working railroad worker, a pioneer advocate for the organizing of unions and workers' rights, and a successful businessman and entrepreneur. Perhaps due to his business acumen (he owned two hotels, a casino, a roller skating rink, and a restaurant), six of his eleven children ran their own successful businesses. My mother, who never met my Abuelito, or "Grandpa" in Spanish, felt a special kinship with him during her married life, prayerfully believing that he was in Heaven watching over the three babies she had lost. (Coincidentally, my mother died 50 years to the day after my Abuelito's death.)

Cayetano Huesca worked for the local railroad in Tierra Blanca, Veracruz (State), on Mexico's east coast. With the demise of the steam engine, there was a lessened need for railroad workers, and the railroad laid off many workers in 1919, Cayetano among them. Needing to feed his wife, Maria Angela Catalina Perrotin (known as "Catalina") and their five children, he moved the family to Orizaba, Veracruz, where he worked for "Ferrocarril Mexicano." The family lived at 48 Calle Abasolo.

In 1923, Cayetano again was laid off. My father, who was about 8 years old at the time, recalls helping his father count the silver pesos he received as severance pay and watching his father cry as he wondered how he was going to support his family.

He decided to move again, this time back to Tierra Blanca. Cayetano found railroad work again, but by now he understood the instability of the changing industry. With the severance he received in Orizaba, he opened a hotel and restaurant, called "El Buen Gusto (Good Taste)." All the children in the family worked in the business. Some washed dishes, while others swept and mopped floors. My father made beds before heading off to school. (To this day, no one makes a bed as well as he did.) There were no allowances but a general satisfaction that all were contributing to the good of the family.

In 1925, with General Plutarco Elias Calles as President of Mexico and a struggle for labor rights beginning, Cayetano Huesca appeared as an actor in a union play, demonstrating the advances made by workers since 1900. Shortly thereafter, he joined other railroad workers in a strike for better conditions. They lost the strike and were fired. As he always did on such occasions, Cayetano went out of his way to feed the strikers, often without charge. Word of his actions spread throughout Orizaba and Tierra Blanca.

One warm morning, he was leaning against the front wall of his hotel, his beautiful young daughter, Victoria, at his side, when a small mob of strike-breakers made its way toward him. Wild-eyed and hungry for blood, the men brandished sticks, guns and knives, determined to make an example of Cayetano. If he was frightened, he did not show it. One of the men caught sight of the innocent Victoria and stopped the others. "Not now, not today," he said. "She shouldn't see this." The men put their weapons down and walked away, never to return. My father used to say that all the younger children of the family owed their lives to their sister Victoria, without whom Cayetano would have surely been killed and they would not have been born.

Despite his bravery, Cayetano was a quiet, gentle man who believed his actions spoke louder than his words. He never had to raise his voice to his children; rather, they knew when they had done wrong just from the look of disappointment on his face. He adored his children and could not bear the thought of having them away from him, even for a night. When my father was about five or six years old, a voice teacher heard him sing and asked my grandfather for his permission to take my father to Vienna Austria, where he promised to train him as a classical singer. Cayetano turned down the offer without hesitation. A child's place was with his parents.

In 1930, Cayetano and Catalina moved their family from Tierra Blanca to Loma Bonita, Oaxaca, where Cayetano leased land to grow pineapples and peppers. They stayed in Oaxaca for three years, moving to Perote, Veracruz, in 1933. There, Cayetano established the "Gran Hotel" - bigger than the "Buen Gusto."

Like his father, he was an officer in the local Freemason chapter. He preferred obscurity to boastfulness and taught his children to “never let your right hand know what the left hand is doing” and that “whatever you do in this life will always come back to you.”

For all his humility, sometimes it seemed that everyone either knew him or knew of him. When I was growing up, I remember that no one spoke of him without a hushed sense of reverence and awe. Cayetano Huesca helped many people, among them a struggling young doctor, José Felipe FRANCO. Cayetano welcomed him as one of his own family, feeding him and helping him establish a small practice in Tierra Blanca.

Some forty or so years later, when my family was living in Mexico City for a time, my sister became quite ill and my anguished parents called a nearby clinic to request that a doctor come to the house to help her. A hunched, stout, man of about sixty years old, with salt-and-pepper hair arrived at our doorstep and was shown in. He examined my sister and exchanged pleasantries with my parents.

When he learned my father’s name, a look of amazement came across face. He excitedly asked if my father was related to Cayetano Huesca. “Then I cannot take your payment, sir,” he said, explaining that my grandfather had helped him years before. Thanks in part to Cayetano’s faith in him, he had gone on to become a successful doctor and a wealthy man, building a children’s clinic and hospital, “Clínica Dr. Franco,” located on Avenida San Cosme near Colonia San Rafael in Mexico City, where he cared for poor children and their families, often free of charge. He and my parents became close friends and stayed in touch until he died in the 1980s.

About six months after Cayetano and Catalina's youngest child, Edilberto, was born in Perote in 1937, Cayetano fell ill with pneumonia. The family decided it was time to move again, this time to Mexico City, where Cayetano entered the Sanatorio Espanol, or the Spanish Hospital. But the treatment of the day was futile, and he died on September 11, 1937. He was 50 years old. He is buried in Mexico City with his wife, Catalina, and three of their children, Enrique, Mario, and Victoria.

Many years after his father's death, my own father visited a friend at the railroad workers' union hall in Mexico City. Recognizing his name, the receptionist asked him if he was the son of Cayetano Huesca. When my astonished father answered in the affirmative, the excited clerk led my father to a large hall, where he found his father's name engraved on a plaque honoring the work he had done to defend the union.

Cayetano Huesca's legacy of devotion, fairness, loyalty and hard work live on today through his children, his grandchildren, and his great-grandchildren, who surely have honored his memory by living lives of integrity, generosity, and charity.

Did you know Cayetano or Catalina (Perrotin) Huesca or their children, or are you a member of the Huesca or Perrotin families? If so, share your memories and comments below.